Monday, January 30, 2006

Thursday, January 26, 2006

There's a Cold Snap A'comin!

I sit on my porch swing, sipping my Mint Julip. The hounds are lolling on the porch with me, heads hung low, pantin' hard and I wonder at the absolutely devlish length of their tongues.

I sit, wondering if all the cotton's done been brought in from the fields and if the ol' plantation will survive one more growing season on just the money my Mama hid under the cornshuck mattress upstairs in Nana's room.

I am dewy with perspiring, and my little fan with pictures of magnolias on it just doesn't seem to be cooling me down. I reckon it to be about 104 degrees and my stays are just about to melt on me. But then I might be able to breath so that'd be jest fine.

My ears perk at the sound of a voice. It's sounds urgent and concerned to the future. It might be something I'm thinkin' I need to hear. It's coming from inside the big house. I rise up and shake out the crinolines - damning my overheated stays that threaten to smother me under my breath.

I simper into the house. Normally I trounce on thru and get Mama all het up at me, but I'm jest too dern warm for that nonsense today. I head on back to the gathering room. Mama's setting with her darnin out and Nana's snoring and drooling in the corner, her sock she's been knitting since the War of Northern Aggression still only halfway done.

I turn toward the urgent and concerned voice I hear. I see the most important gentleman in the neighborhood is with us. The one we listen to constantly. The one who imparts the most needed and helpful news to us as quickly as he can. We always listen to this man.

Slowly I sink down onto the cushion, wishing I could be rid of the stays and breath a little. Mama's telling me to hush up and listen, all the while handing me a lace hankie as she deems me to be a little "too dewy" for a true lady.

I turn to the voice. He has urgent news he tells us. Very important. He informs us to cover our vines and bring the animals in from the lower fields. There's a COLD SNAP coming! Right quick! We could be in for some serious chills.

My goodness, it might be as low as 89 degrees tomorrow!

I turn off the television and the weatherman and head upstairs for a sweater.

I sit, wondering if all the cotton's done been brought in from the fields and if the ol' plantation will survive one more growing season on just the money my Mama hid under the cornshuck mattress upstairs in Nana's room.

I am dewy with perspiring, and my little fan with pictures of magnolias on it just doesn't seem to be cooling me down. I reckon it to be about 104 degrees and my stays are just about to melt on me. But then I might be able to breath so that'd be jest fine.

My ears perk at the sound of a voice. It's sounds urgent and concerned to the future. It might be something I'm thinkin' I need to hear. It's coming from inside the big house. I rise up and shake out the crinolines - damning my overheated stays that threaten to smother me under my breath.

I simper into the house. Normally I trounce on thru and get Mama all het up at me, but I'm jest too dern warm for that nonsense today. I head on back to the gathering room. Mama's setting with her darnin out and Nana's snoring and drooling in the corner, her sock she's been knitting since the War of Northern Aggression still only halfway done.

I turn toward the urgent and concerned voice I hear. I see the most important gentleman in the neighborhood is with us. The one we listen to constantly. The one who imparts the most needed and helpful news to us as quickly as he can. We always listen to this man.

Slowly I sink down onto the cushion, wishing I could be rid of the stays and breath a little. Mama's telling me to hush up and listen, all the while handing me a lace hankie as she deems me to be a little "too dewy" for a true lady.

I turn to the voice. He has urgent news he tells us. Very important. He informs us to cover our vines and bring the animals in from the lower fields. There's a COLD SNAP coming! Right quick! We could be in for some serious chills.

My goodness, it might be as low as 89 degrees tomorrow!

I turn off the television and the weatherman and head upstairs for a sweater.

Sunday, January 15, 2006

"Cowgirl Up!"

Pattie in Pearl Snaps

My readers have been served up this old photo for a couple of years now, but the Cowtown Fat Stockshow always calls for another posting. The year was about 1959, and as you can see, I am not wearing cowboy boots. They hurt my feet and I refused to wear 'em. Have a couple of pair now, but back then I can remember pitching a hissy fit about the way they looked and felt - stiff, unwieldy and plain ugly to me. White patent leather maryjanes were the ticket.

Kman and I just got back from our yearly trip to the stockshow this evening. The exhibits pretty much stay the same, but the ticket prices have skyrocketed: $6 to park and $8 just to get in the gates. Rodeo tickets are $25 for the cheap seats.

We stopped for a bit to watch an auctioneer go through his musical scales while trying to get the best bid on a mama longhorn and her calf - $2700 for the pair. I love hearing an auctioneer with his effortless rolling of words, but I have never had the nerve to actually participate in a live auction. Looks like you could get stuck paying far more than you intended; by the time I might find enough gumption to stick my hand up, the auctioneer would have added at least a thousand more dollars to the bid. Those guys are certainly silver-tongued.

People watching is no small part of the stockshow experience. Best laugh of the night - a little cityslicker cowboy about three years old obviously a little tired of waiting on the parents who were engaged in long conversation with friends, wrangled his own snack from a nearby wheelbarrow full of cow feed. He was munching away on some of it when finally Mom looked down with more than a little dismay. The old rancher who was feeding his stock just laughed and said, "Ma'am it's mostly corn and oats, just make him grow good."

The youngsters that groom and care for their animals all year long can win a lot of money for the effort. Many college degrees have been paid for by Elsie or Vindicator, but it's tough to watch the young faces when they have to finally give up their much-loved animal. I don't think I could do it. I have great admiration for these kids and wished I could have given such an opportunity to my own brood of chicks. Alas, the only ranch we ever owned was in a salad dressing bottle.

Kman said after tonight and we win the lotto, I can go back and give that auctioneer a run for his cattle...I might even wear my boots.

Saturday, January 14, 2006

The Lost Sea in Sweetwater, Tennessee

When I was a child growing up in Alabama, my parents used to take me and my sister camping in the Great Smokey Mountains. We would see Gatlinburg, Pigeon Forge and many of the attractions located there.But one place I always wanted to go, we never made it to: The Lost Sea.

The Lost Sea is located in Sweetwater, Tennessee, right off I-75 between Knoxville and Chattanooga, and is known as "America's largest underground lake".

The caverns are rich in geological formations such as the "cave flower", known scientifically as anthodites. The website says "These fragile, spiky clusters commonly known as "cave flowers" are found in only a few of the world's caves. Their abundance in Craighead Caverns led the United States Department of the Interior to designate the Lost Sea as a Registered National Landmark, an honor the Lost Sea shares with such unique geological regions as the Cape Hatteras National Seashore in North Carolina and the Yosemite National Park in California."

The website also states that the anthodites are so rare, that the cave hosts "50% of the world's known formations".

The underground lake itself is immense, covering about 4 1/2 acres, much of it inaccessible. Vistors can take a glass-bottom boat tour where you will see large rainbow trout swimming in the lake's crystal clear waters.

The cave has a very interesting history as well. Tour guides tell guests of the Cherokee Indians who once used the cave, an giant Pleistocene jaguar who once became lost in the caverns and fell to it's death - it's bones much later found and displayed in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and how the cave was used by Confederate army during the Civil War to mine the cave for saltpeter, "a commodity necessary to the manufacture of gunpowder". The cave was also used by moonshiners during Prohibition.

Outside the cave you will find shaded log cabins housing the General Store, an ice cream parlor, a glassblower's and a Trading Post.

Tours are given to the general public during the day, every day of the year except Christmas. There is also a Wilderness Tour offered to groups of 12 or more, such as scout troops, church groups, etc... It is an overnight tour with some grubby crawling through tiny spaces in the cave and ending with a camp-out in the cavern itself.

For more information such as pricing and hours of operation, visit the Lost Sea's website at http://www.thelostsea.com/home.htm. I know we're headed there this summer and I can't wait!

**photos courtesy of www.thelostsea.com

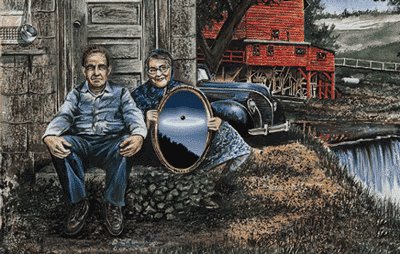

Saucers in the Valley

Maybe it was because he had been deep in thought, pondering what to do about his youngest, Varnella, who had been driving him and his wife crazy moping around the farmhouse and pining for her on-again, off-again, so-called fiancé, Billy Tom.

Maybe it was because he had been distracted by the old pickup's AM radio--the New Orleans radio station's signal, although powerful at night, sometimes had trouble making the giant electronic leap over the mountains into his Tennessee valley, and DJ Charlie Douglas was sounding less like the Voice of the American Trucker and more like a staccato ad for white noise.

Or maybe it was because he was not accustomed to being at the far end of his property, what he called the upper forty, this late at night in the middle of July--a few of his cattle had made it through a narrow gap in the wooden fence, and he had tracked them to that pasture at the foot of the mountain.

Whatever the reason, Varnell was snapped out of his complacent trance by the bright swirling lights and the menacing electronic hum as the two aircraft hung low over the far end of the pasture where it met the mountain woods. He blinked several times, and rubbing his eyes, he jumped out and stood in front of the idling pickup, and was silhouetted in the yellow glare of the dim headlights. They looked like big shiny pot lids, he thought, similar to the one Varnella had used that afternoon to cover the green beans she had snapped before running out of the kitchen in a Billy Tom crying jag. But these were much larger pot lids, with spectacular running lights, and one of them toggled back and forth in what Varnell interpreted as some sort of salute as he stood in the pickup's makeshift spotlight. After hovering low over the pasture for a minute--he could see the missing cattle frozen stupidly in the glow of their running lights--the two gleaming objects abruptly shot up vertically several hundred feet in tandem and disappeared into the summer night sky.

Varnell stood there mute as the old pickup behind him sputtered, and the headlights dimmed and brightened in rhythm with the engine. The radio jumped into focus with Charlie Douglas's familiar voice cutting through the humid night. "That was The Blue Sky Boys coming to you wherever you are from way down here in New Orleans!"

Varnell quickly gathered himself and swung back behind the wheel of the truck and ground it into gear, kicking up dust which turned red behind the cracked taillights and leaving the errant cattle to their private stupors. He tore out of the upper pasture, cut across part of the garden and through the chicken yard, and hit the dirt-and-gravel driveway in high gear, fishtailing as he rounded the bend by the farmhouse. His wife, Ruby Nell, and Varnella were in the swing on the front porch, and they watched him with open mouths as he flew by the house, on down the driveway and onto the main road at the bottom of the hill. "Well, I…" said Ruby Nell.

Once on the valley road, which ended at the main highway that led into the small town, Varnell began to collect his thoughts and rehearse his story. It did sound far-fetched, he thought. The radio started to crackle and hiss again, but he didn't even notice. Before he knew it, he was rolling onto the town square and pulling up in front of the police station. He parked the pickup and hurriedly climbed the steps and threw open the frosted-glass front door. Just inside, in the lobby, Sheriff McAnnally was leaning back in his black wooden office chair with his crossed boots stretched out across his cluttered desk. He held a torn newspaper in one big paw, and scratched at his slick black thatch of hair with the other. On the desk was a small electric fan which whirled noisily, fluttering the "1974 Girls of the Appalachians" calendar on the wall behind him.

The two men had known each other for most of their lives. They had actually been friends once, around the second or third grade, but with the advent of football in McAnnally's world, and 4-H and Future Farmers in Varnell's, the two had been distant since junior high. In high school, their only communication had been when McAnnally greeted Varnell rudely in the hallways with a swift and powerful punch to the arm. This particular night, he glanced up slowly as Varnell came to rest in front of the desk.

"As I live and breathe…Varnell Pugh. What brings you out on a hot summer night in the middle of the week?" he said, looking back down at his paper.

"Uh, hey Sheriff," Varnell began. "Uh, I just saw something real strange.

"Yeah? What's that?"

"One of them AFOs."

"What in the Stamp Hill is a AFO?" said McAnnally quizzically. "Sounds like a Yankee social club."

"Alien Flying Object," Varnell said excitedly, "Martians…I don't know. Up on my land, right there where it meets the park boundary at my upper forty."

McAnnally, suddenly interested, folded his paper and sat up in the wooden chair. "That so? Tell on, Varnell."

"Some of my cattle got through the fence again," he began, "and I got a late start, but I followed their tracks up to the upper forty. I wudn't payin' too much attention, I guess, but once I got up there and started lookin' around, something shot up around the tree line. Real quick-like." Varnell held out his hand, straight and palm down in a clumsy, almost comical imitation of what he had seen. "Saucers. Two of 'em."

"You weren't on county park land, were you, Varnell?"

"I wudn't. I saw them from my field, but I sure can't vouch for them saucers. I don't know where they been or they goin'."

McAnnally massaged his temples with his big right hand. "You sure about this, Varnell?"

"I know what I saw."

"Okay." The sheriff sighed and pushed back from his desk. "Kenslow! Git in here!"

A skinny deputy stuck his head in the doorway. "Yessir, boss!"

"Kenslow, could you please es-cort our friend, Varnell here to holding number three."

Varnell looked at Deputy Kenslow and then back at McAnnally and thought, what kind of a fool joke is this? It's late and I got to get home. That dad blamed McAnnally.

"Varnell," said McAnnally, "we needs to get some paperwork fixed, and I, of course, got to get what we call a formal statement from you, so if you would be so kind as to just wait a few minutes in our, uh, formal statement room, we would ever so much appreciate it."

"But…" Varnell said, confused. He looked back over his shoulder as Deputy Kenslow took him by the arm and led him out of the lobby and toward the back of the building.

"Thank you, Varnell," McAnnally called out after him, his thin lips pursed in a forced smile. "Be a good citizen, now."

Varnell felt tired and dazed. He had been up since four that morning. He should be in bed now. He should have been in bed hours ago. He's never going to get to sleep now. He didn’t even tell Ruby Nell where he was going. She was going to be real mad. And Varnella was probably still on the porch crying. That Billy Tom, he thought, I'm going to have to kill him just to make our lives halfway normal again. He was looking at white concrete and thinking of that worthless Billy Tom.

The loud clang of the cell door behind him jarred him back to reality. Their formal statement room sure looks like a jail cell, he thought wistfully. Think. Think. Think, Varnell, you dad blamed fool. He began mentally retracing his steps and the events of the evening. Okay, let’s recollect. Were you speeding? Come on Varnell, not in that old truck! Did you run the stop sign? Why would I care on a night like this? Did you pay that parking ticket? Good grief, that was three years ago. None of his questions made sense. Then Varnell started thinking about what he had said and how his story must have sounded. That fool McAnnally has got to know that anything is possible out there in the valley. Especially on a summer night when every living thing is hot and miserable, inside and out. He has to be familiar with that part of the county. In fact…

Varnell stopped mid-thought and sat down on the little bed in the holding cell. Come to think of it, he had seen the sheriff's patrol car driving by the house late at night--always on nights when he couldn't sleep. On nights when he could sleep, the sheriff and his posse couldn’t have roused him with lights on and sirens blaring. Right at that moment, however, there were fuzzy pieces of a big puzzle in Varnell's mind, and they were shifting in and out of focus, connecting and flying apart. He had always been something of a dreamer, but it had been years since he had gotten into trouble over it, and trouble had never meant being locked up the county jail. Then suddenly a picture of a moonshine still came into focus in his brain.

"Dad blame, that's it," he said. Everyone in the county knew about the rumors of McAnnally and moonshine. Some people said he looked the other way in return for a piece of the action; others said he was the action.

And some even said that his moonshine operation was somewhere on the park land owned by the county--land that was off limits to the public…land that butted Varnell’s property.

"That dad blamed buzzard problee thinks I'd lead ever-body, friend and foe, up to that park land," said Varnell out loud, "That’s exactly what he thinks. Newspaper reporters, TV newstypes, and every crazy AFO freak in the county--the state for that matter--all climbing over his dad-blamed moonshine still looking for Martians. It'd be pretty durned funny if I wudn't laughing inside one of his cells. Deputy! Yo, deputy!"

"Stop yer hollerin'. What you want?" Deputy Kenslow came over to the cell wiping peanut butter off his upper lip.

"I want you to go git the sheriff."

"You want to make a statement?"

"You might say that. Jest go git him."

From the other side of the door, Varnell heard their muffled conversation, but he couldn't make out what was being said. He could tell, however, that someone, probably the sheriff, was loud and upset. Sometime later, McAnnally slowly rounded the corner. "What is it, Varnell?"

"Sheriff, can we talk?" Varnell had calmed down at this point, and had even practiced his speech.

"Why, of course, Varnell. We're all friends here."

"I gotta say, Sheriff, it took me by surprise, you throwin' me in here…"

"You mean in the formal statement room? That was for your own protection, Varnell."

"Look, Sheriff, I got a pretty good idea why I'm in here, and a prettier good idea about why you're so concerned about that park land up by my upper forty."

The relaxed grin left McAnnally's face and was replaced by a forced smile. "Yo, Deputy, gimme your keys a minute."

Kenslow obliged and then stepped back behind the sheriff.

"Leave us," the sheriff said, turning his massive gaze on the hapless deputy.

Once Kenslow quickly shut the door to the hall leading to the holding pens, McAnnally turned back to Varnell and began fidgeting with the key in the lock. "Do proceed, Varnell."

"Okay. Maybe you got some kind of interest in that property. I don't know. It ain't my business."

"What kind of interest do you think I have, Varnell?" The sheriff had the cell door open wide and was leaning against the bars on the inside, almost daring Varnell to make a run for it through the open door.

"Well, there's always been talk…"

"Talk? What kind of talk, Varnell?"

"Like I said, it ain't none of my business, but, you know, talk of moonshine."

"Varnell! This is a dry county. And I’m sheriff of this here dry county."

"Sheriff, I ain't accusing nobody of nothing. All I'm saying is if you put me in here…"

"In protective custody…"

"…whatever. For whatever reason. If that reason was that you was afraid I was gonna tell folks about what I saw, and those folks started coming up to my pasture and onto the county park land…"

"First of all. I ain't afraid of nothing, 'specially nothing little ol' you could stir up. Secondly, that up there is county land. It is off limits to the people. It is a protected area."

Just then the door leading to the cells opened and a large man in green scrubs with "STAPH STAFF" stenciled on the front stepped under the swinging light bulb in the narrow hall.

"Whoa, now!" said Varnell turning white, "I ain't no STAPH looney!"

The large man turned his back to Varnell and McAnnally and proceeded to fiddle with something in his attaché case. When he turned, Varnell could barely make out the embroidered type on the back of the man's scrubs: Southeastern Tennessee Area Psychiatric Hospital. Varnell opened his mouth to protest, but McAnnally quickly jackhammered his huge fist into Varnell's right arm, spinning him around and driving him to the floor of the cell.

"Just like old times, eh, Varnell?" he said, and then he turned to the huge man in the scrubs. "There. I softened it up for ya."

The small cell was swirling around Varnell's head, and it all went dark for a second, but when he opened his eyes, the man in the scrubs already had the needle in his arm. "Hey! That's not necessary, you!" he said. But the man ignored him and efficiently finished up, wiping Varnell's arm with an alcohol swab.

"'Hey,' I said," Varnell complained, rubbing his right arm.

"Go on out there," McAnnally told the man, his back to Varnell. He thumbed in the direction of the outside lobby. "Wait for us. We'll be right out."

The man nodded and collected his attaché, leaving as quickly as he had arrived. Varnell knew he should somehow make his move. Bust McAnnally in the chops and sail on out of there. They left the doors open! You could grab his gun…nobody would stop you. But he just sat there staring up at the glaring sheriff.

"Here's the thing, Varnell," the sheriff said slowly. "I gotta hand it to you. You were right on the money…I do have interests up there. Not too far from your land. In fact, right on the other side of that ridge above your property…just out of sight. And you were right again on the moonshine. We make it and we sell it. But what you didn't know is who we sell it to. That's the big secret. Or it was the big secret until you saw 'em."

"Saw who?" Varnell slurred.

"My biggest clients. And they ain't Martians…they's Venusians."

"Ven-youshee whats?"

"Venusians, Varnell. Boys from Venus. They's a long way from home. But they love the 'shine. Their ship runs on it! They say it's better than gasoline or diesel, or better even than their nuclear stuff. Ain't that a hoot!"

"Hoot!"

"Come on, Varnell, they're waiting."

Varnell slowly got to his feet and walked out of the cell with McAnnally behind him. "This sure turned out to be a real interesting night," he said.

"I hear you," said McAnnally.

Out in the lobby, Varnell was surprised to see Ruby Nell sitting at the sheriff's desk filling out some papers. She was as pretty as the day he married her. Varnella was there behind the desk in front of the sheriff's calendar, waving as they walked through. To her right was Billy Tom, and he was tuning his guitar. Some of his long-haired friends were next to him with their banjos and fiddles. Deputy Kenslow had changed clothes and was playing mandolin on the other side of Billy Tom. They were all dressed alike.

Once Varnell and the sheriff got to the middle of the room where the big man in the scrubs stood waiting, the musicians started in on a Blue Sky Boys tune as if on cue. "They ain’t half bad," Varnell thought. "Matter of fact, they're good…real good!"

Behind the musicians, the walls had been freshly painted with a scene of a big oak tree in a grassy field on a beautiful August late afternoon. And to Varnell's surprise, there was his Aunt Edna under the oak tree carrying a plate of her fried chicken. "Ain't you been dead ten years, Aunt Edna?" Varnell asked.

"Varnell, you come over here and have a piece of this chicken, and you tell me."

Varnell plopped down on the blanket in the wet grass, and with his fingers laced behind his head, he gazed up dreamily at the afternoon sky. The warm breeze tickled his cheek and hissed through the branches of the big oak tree, shaking loose a lone Mockingbird, whose outstretched wings were lit up by the sinking sun.

www.southernreader.com

dskinner@SouthernReader.com

To hear the song, "Saucers in the Valley," (the file is 1.2 MB and takes a few minutes to download with a dial-up connection) go to: http://www.SouthernReader.com/SaucersInTheValley.MP3

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

©Copyright 2004 David Ray Skinner/SouthernReader. All rights reserved.

Wednesday, January 11, 2006

Reasons Why I Live in the South

The term South is defined as the region of the United States lying south of the Mason-Dixon line. That is just a tad vague, so how about this one? The region of the United States including Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Missouri, Arkansas, Florida, West Virginia, and eastern Texas.

Now that we know where the South is, I'd like to expound a bit on why I live here. For one, I was born and raised in the South. North Carolina to be exact. For four years, from 1976 to 1980, I ventured outside the South because of my husband's job. We ventured FAR from the South to Frankfurt, Germany, where we were unusual not only because we were Americans, but because we were Americans with a strange accent. I remember being asked to speak just so folks could listen to my accent. Depending on how nicely they asked, and whether they were snickering when they asked, I'd comply. Of course in London, I did the same thing -- asked questions of shopkeepers and folks on the street just to hear the different British accents.

When we left Germany, we were given the choice to return to any place in the US where my husband's agency had a branch office. This included Washington, DC, Boston, Chicago, Denver, San Francisco, Seattle, Atlanta and Dallas, along with a number of towns with satellite offices. Where did we choose? Tiny Huntsville, Alabama. We'd lived here for a year prior to our overseas move and felt it was a great place to live and raise a family. We've turned down several chances to move to other places because we love it here, though we are pondering relocating somewhere else when we retire. The places we've considered, however, are still in the South.

So why, other than my husband's job, do I live in the South? In no particular order...

- Southern hospitality - an undefinable quality, but you know it when you've experienced it

- Fried anything

- Sweet tea

- Sweet potato pie

- Black-eyed peas (remind me to tell my black-eyed pea story)

- Country ham

- Gravy -- red-eye and sawmill

- Grits

- Quaint phrases

- Peaches and peach cobbler

- Pecans

- The Florida panhandle beaches

- Magnolias and dogwoods

- Barbeque

- Crawdads

- Peanuts

- Fried green tomatoes (I felt these deserved their own entry cause they're so good)

- Corn on the cob

- Sunday lunch with the family

- Biscuits

- Shagging at Myrtle Beach -in case you're a Yankee reading this, that's a dance ;-)

- Fried pies (again deserving of its own entry)

- Yard sales and flea markets

- The Grand Ole Opry

- The Smoky Mountains

- Kudzu (well, not really, but it IS a definitive part of the South)

- The Blue Ridge Parkway

- Charleston and Savannah

- That religion called college football and/or basketball

- Front porches with swings and rocking chairs

- Drives through the country on Sunday afternoon (not so common nowadays with the current price of gasoline

- Jeff Foxworthy

- Hot'lanta

- Alabama, Bo Bice and Hank Williams

- Biltmore Estate

- Southern belles

- Rhett Butler

I asked my sister if she had any thoughts on the subject and she contributed five really GREAT reasons.

- I don't have to explain my accent

- People don't think I'm stupid because of my accent

- I don't have to shovel snow (not true in all parts, but it's been a looooong time since I've seen snow too)

- I can wear the same clothes year-round (again, not true in all parts. She's on the Georgia coast, I'm in north Alabama and I definitely have summer and winter wardrobes)

- Young children (and old children) call me "Miss Bev" even though I'm beyond the age of being a "Miss"

I'd hoped I could come up with 50 good reasons, and I suppose if I listed all the fried things individually, I could stretch it out.

What makes the South special to you? Add to my list and let's see if we can get it to 50 or beyond.

The Black-Eyed Pea Story

I mentioned that we lived in Frankfurt, Germany for four years. We lived in an apartment complex filled with other Americans who were employed by various governmental agencies. Most were Yankees but a few of us Southerners had squeaked in.

My upstairs neighbor was a good Catholic woman from Erie, Pennsylvania. One day she appeared at my front door with an open tin can. "What do I do with these?" she asked as she shoved the can in my face. Inside the can were black-eyed peas.

"Just put them in a pot and warm them up," I told her. "Then eat them."

"Oh," she replied. "I really wasn't sure what to do with them."

Not sure what to do with black-eyed peas? Seemed a little odd to me. So I pursued the subject a bit.

Army commissaries often have food in plain silver cans with no label. The only marking is black stenciling on the top of the can. This particular can had the following "code" on the top: B-Eye Peas. Simple enough, I thought. Well... not to a Yankee.

"I thought I was buying Bird's Eye Peas," she explained, not thinking that Bird's Eye is a brand name and not a type of pea.

"Nope, you bought black-eyed peas. You might want to throw a little ham in there to season them up. That'll make them taste even better."

And that is the black-eyed pea story. It was a lot funnier if you were there.

Another time I'll tell about giving lessons on how to fry chicken. Actually, there isn't much to tell except that a couple of Yankee gals asked me to teach them how to fry chicken. End of story.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)